What You’ll Find This Week

HELLO {{ FNAME | INNOVATOR }}!

In Part 1 of How to Budget for Innovation, we outlined the key difficulties innovators encounter when trying to budget for their work, especially when those efforts don’t align to traditional corporate KPIs. This week, in Part 2, we’re following that thinking with ideas on how to effectively budget for your innovation efforts and how to align organizational thinking to metrics that support your efforts.

Here’s what you’ll find:

This Week’s Article: How to Budget for Innovation | Part 2: Executing the Innovation Budget

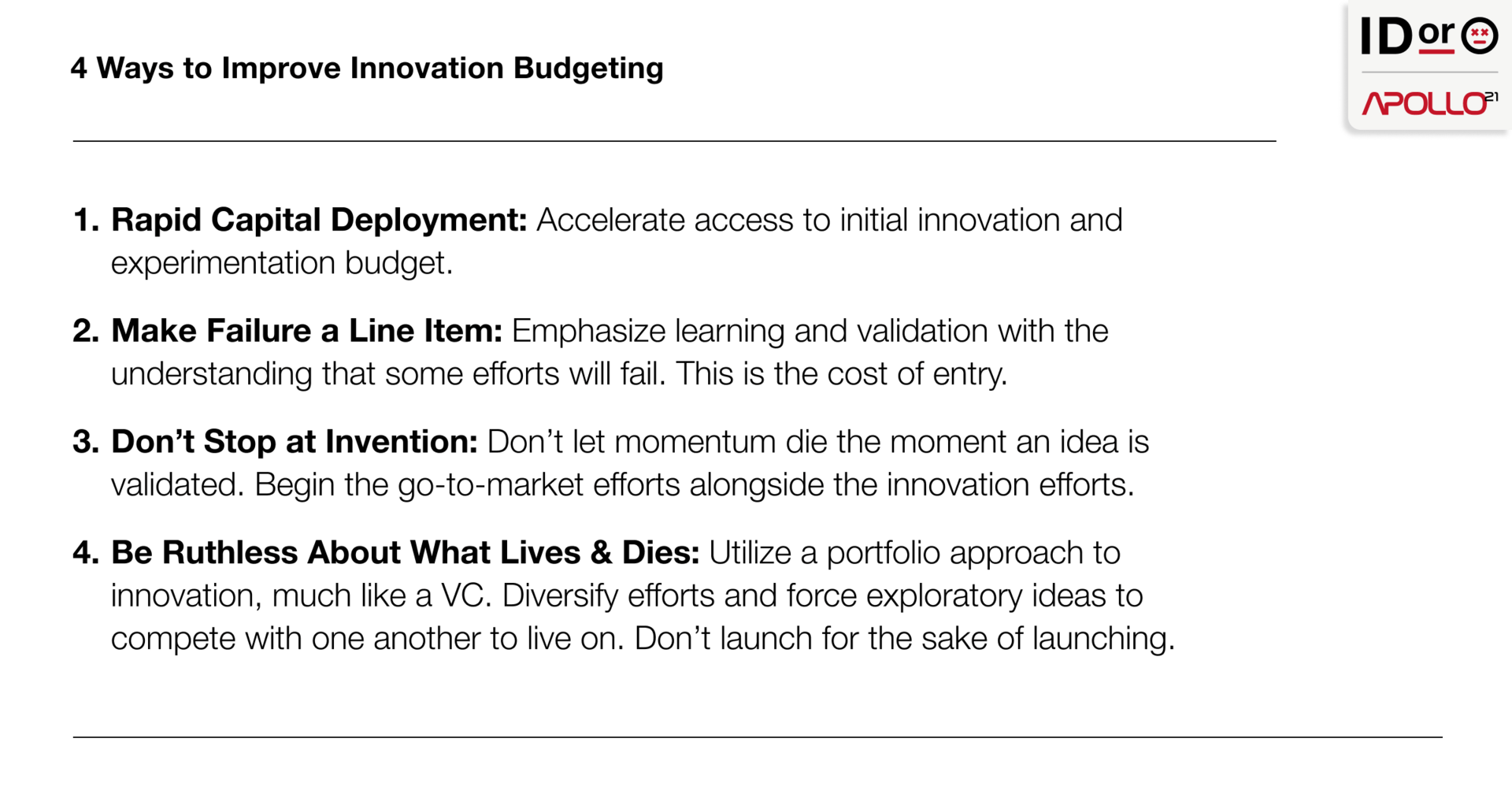

Share This: 4 Ways to Improve Your Innovation Budgeting

Don’t Miss Our Latest Podcast

This Week’s Article

How to Budget for Innovation

Part 2: Executing the Innovation Budget

In Part 1, we laid out why most companies fail at innovation budgeting: they treat it like core operations. Innovation needs different structures, governance, and metrics. This is where execution usually breaks down. But knowing that doesn’t help if you can’t put better budgeting into practice.

Many companies publicly commit to innovation but then rely on ad hoc funding, inconsistent governance, and off-the-books resourcing. Interviews and industry case studies from McKinsey, EY, and others have surfaced patterns of fragmented innovation funding: projects funded through scattered line items, under the radar of centralized oversight, or cobbled together from discretionary business unit spending.

This outcome is what some leaders refer to as a "shadow budget." Disconnected from core financial planning, poorly defined, rarely tracked, and often divorced from real strategic priorities, it creates confusion internally and undermines credibility externally. This behavior is common when innovation isn’t embedded in capital planning processes or assigned its own governance mechanisms.

To run innovation with the same discipline and intentionality as a venture portfolio, you need budget governance that supports action, iteration, and accountability under conditions of uncertainty. That requires operational rigor to support your org’s big ideas.

Today we’ll focus on the execution layer: how to allocate, monitor, and adapt the innovation budget in real time. Strategic option value, fast learning, and scalable results don’t happen automatically. They emerge when execution is resourced and structured correctly.

Design Budgets for Rapid Deployment

Moving fast requires removing friction from decision-making, reducing dependencies, and giving teams the authority to act. That starts with how you fund them.

In most companies, even a modest budget request for an innovation initiative has to follow the same rigid process used for major capital expenditures: lengthy business cases, multilayered approvals, and legal/procurement gauntlets. These processes are optimized for risk reduction, not discovery. By the time the money shows up, the idea is dead. Or worse, a competitor has already launched it.

Orgs that are adept at fast-tracking experimentation have access to:

Pre-approved capital pools: Dedicated early-stage funding that bypasses the annual cycle.

Lightweight approval processes: Streamlined governance with empowered cross-functional teams.

Small, fast checks with follow-on tied to discovery milestones: Funding tranches based on what’s learned, not just what’s planned.

The sooner a team has resources, the sooner they can test, learn, and pivot. The point of these enablement processes isn’t to deploy an abundance of capital upfront; it’s to reduce time-to-first-dollar.

Execution begins with access.

ABB Technology Ventures, the venture arm of ABB (who we covered in our mini case study in Part 1), makes this principle operational. It has a dedicated investment team with autonomous capital and streamlined governance, enabling faster investment decisions. That speed matters, even in deeptech (which is ABB’s area of focus), where development cycles can be long and complex. Early access to capital helps teams secure partners, accelerate feasibility work, and build momentum before competitors do. In high-stakes categories, the ability to deploy capital quickly becomes a strategic asset, not just a procedural step.

One of the most critical (and most common) bottlenecks in the innovation process stems from ineffective allocation of resources—not because of insufficient funding but rather because of unclear or inaccurate definitions of how resources will be deployed and what kinds of returns they are expected to generate. This can result in low-performing initiatives being funded at the expense of higher-performing ones or critical initiatives failing because some teams deliver on their work while others don’t.

Make Failure a Line Item

If your budget doesn’t expect failure, you’re not going to be “doing” innovation for long. Failure isn’t a surprise. Failure is a signal.

The goal is to learn fast and cheap, not to avoid every misstep. That means setting aside a portion of the budget as a learning buffer: capital you expect to spend on things that won’t work. This isn’t waste. It’s tuition. It’s the cost of entry.

Companies that succeed at innovation:

Track "cost-per-insight" not just cost-per-output: Learning becomes the currency of early-stage work.

Reward teams for fast kill decisions: Progress isn't just about forward momentum—it’s about knowing when to stop.

Review what was learned, not just what was built: Retrospectives should focus on insight, not just delivery.

Failure budgets also enable portfolio thinking. If you’re funding 10 bets, you expect 6 to fail, 3 to survive, and 1 to scale. Without a structure that makes this explicit, most orgs either overfund too many things or pull the plug before real learning happens.

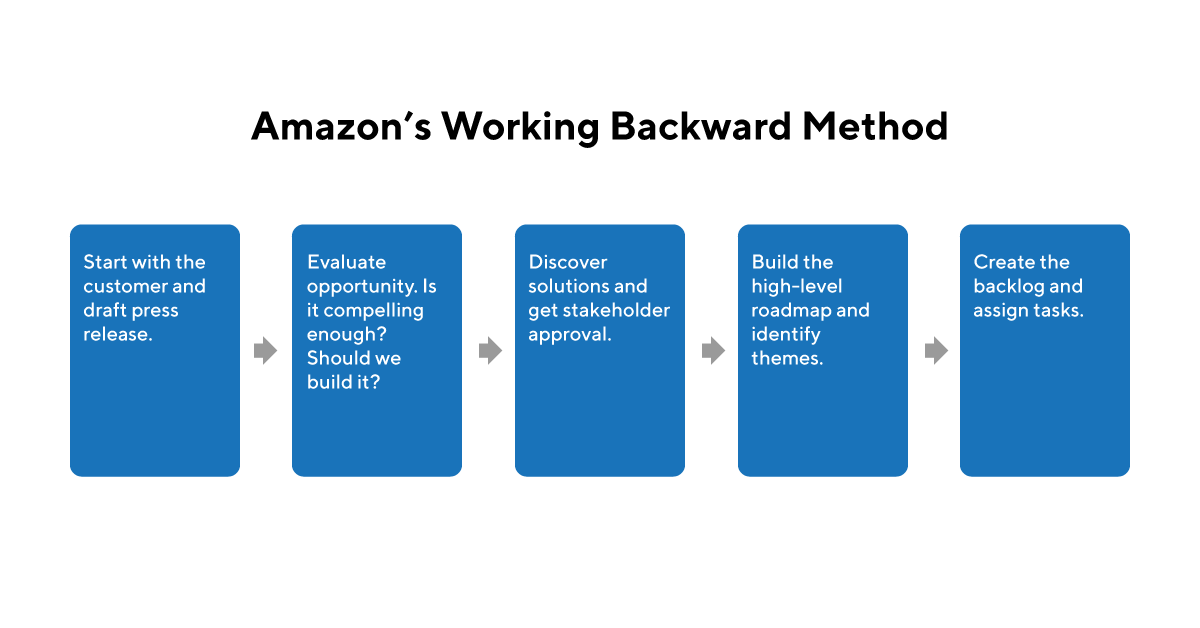

Amazon institutionalized this through its "working backwards" process. Teams draft a future press release and FAQ before development begins. If the customer value can’t be clearly articulated, the idea doesn’t move forward. It’s a pre-mortem filter that prevents bad bets from getting funded.

Innovation Doesn’t Stop At Invention

Most corporate innovation budgets over-index on early-stage activity: discovery, prototyping, proof of concept, while leaving a fatal gap between validation and commercialization. This is where momentum dies. Teams prove an idea works, but then find there’s no funding or ownership to bring it to market.

To bridge the gap, budget must deliberately support commercialization milestones. This means:

Dedicated funds for go-to-market: Allocate capital not just for development, but for the commercial enablers that follow: channel design, pricing validation, customer onboarding, and pilot scaling.

Embedded commercialization expertise: Treat go-to-market planning as a parallel track from day one. Assign resources from marketing, sales, and customer success during incubation, not after.

Defined transition criteria: Build the handoff into your budget model. Have pre-aligned requirements and funding triggers for when and how a venture moves from incubation to scale.

The best innovation teams don't just test for technical feasibility. They validate desirability and viability with the same rigor, and they budget accordingly. If you only fund invention, you’re subsidizing a pipeline of dead ends.

Startups instinctively understand this. They bake GTM into the business case from the beginning, often using content, partnerships, and earned media to build traction before the product is even live. Corporate innovation efforts should borrow this mindset. Budget for customer validation the same way you budget for technical feasibility. Fund the bridge between demo and demand.

Be Ruthless About What Lives & Dies

Innovation portfolios should be dynamic. Yet too many companies fund projects indefinitely, more afraid of admitting failure than wasting capital. Budget discipline means actively choosing what to fund…and what to kill.

That requires:

Milestone-based funding with explicit go/no-go gates: Every initiative should be structured around staged gates, each with predefined expectations and decision points.

Pre-agreed metrics that define success at each stage: Success needs to be measured against known indicators, not vague aspirations.

Scheduled reviews with cross-functional accountability: Reviews should occur on a fixed cadence and include stakeholders from across the business.

Studies show top innovators actively kill 20–30% of initiatives within six months of launch rather than waiting years for results. By building explicit "kill thresholds" and tracking the idea-kill rate as a KPI, organizations mirror venture-capital discipline rather than treating innovation as a side project.

Good innovation teams shut down ideas regularly as part of their process. They view it not as failure, but as capital reallocation. The goal is to move quickly through uncertainty and avoid continued spend on projects that no longer merit it.

You can reduce the odds of placing bad bets through better decision-making processes and closer scrutiny of assumptions. This was the case for a global CPG company that was frustrated its innovation “funnel” had become a “tunnel” where flawed initiatives proceeded to market despite misgivings from both the teams and leaders, and resources were rarely reallocated between initiatives.

In response, the company shifted its governance and resource-allocation approach and borrowed leading practices from venture capital. These included “investor boards” empowered with decision rights on what to fund and what to cut, and metered funding that allocated resources in increments based on demonstrated performance. Within six months, the company redirected 30 percent of its initiatives dramatically and killed another 20 percent (including a nationwide launch that company leaders recognized was highly likely to fail).

Conclusion: Budget IS Strategy

An innovation budget is a reflection of intent. It shows where leadership is willing to invest time, tolerate uncertainty, and demand results. It sets the boundaries for experimentation, the pace for learning, and the structure for accountability.

If innovation is supposed to drive growth, then the budget has to support every stage of that growth from zero to revenue, from questions to insight. That means designing budgets for agility, building in room for failure and iteration, and making room for exit ramps, not just runways.

Effective budgeting doesn’t chase certainty. It funds optionality.

It doesn’t wait for full validation. It creates conditions for discovery.

And most important, it doesn’t operate in isolation. It connects innovation to the rest of the enterprise, financially, operationally, and strategically.

Done well, an innovation budget:

Supports disciplined exploration: Innovation involves unknowns, but budgets should still apply controls through staged funding, defined milestones, and clear exit criteria.

Links capital allocation to learning: Budgets should support iterative cycles that generate insight, not just results.

Builds the financial foundation for repeatable, scalable innovation: Consistent funding models enable long-term capability building across the innovation lifecycle.

Aligns strategic ambition with operational execution: Clear funding priorities ensure innovation isn’t siloed—it’s embedded in the broader enterprise agenda.

The innovation budget is a signal to the rest of the organization. It tells people what kind of risk is acceptable, what kind of outcomes are expected, and what kind of speed is required. If it looks like everything else, expect more of the same.

If it’s designed for the future, it might actually help build one.

Share This