HELLO {{ FNAME | INNOVATOR }}!

Ever wonder how a tire company became the world’s leading curator of restaurants? (In case you didn’t know, yes, the Michelin tire company invented the Michelin stars that chefs worldwide strive to acquire.) What most people miss is that it wasn’t a branding exercise for Michelin. It was a behavioral play. And one of the most effective demand engines in the history of modern business.

This week, we break down how Michelin used cultural infrastructure to create a market and underpin their buyers’ most important Job to be Done. How they built a product that reshaped the restaurant industry while still feeding the core. And why the Michelin Star remains one of the clearest examples of venture-driven growth a corporate has ever pulled off.

Here’s what you’ll find:

This Week’s Article: The Perfect Innovation Doesn’t Exis…

Case Study: How Red Bull borrowed from Michelin’s genius.

Share This: The Growth of Car Ownership in Early 1900’s France

The Perfect Innovation Doesn't Exis...

Why One of the Most Successful Demand Gen Plays in History Wasn’t a Marketing Stunt. It Was a Venture Strategy.

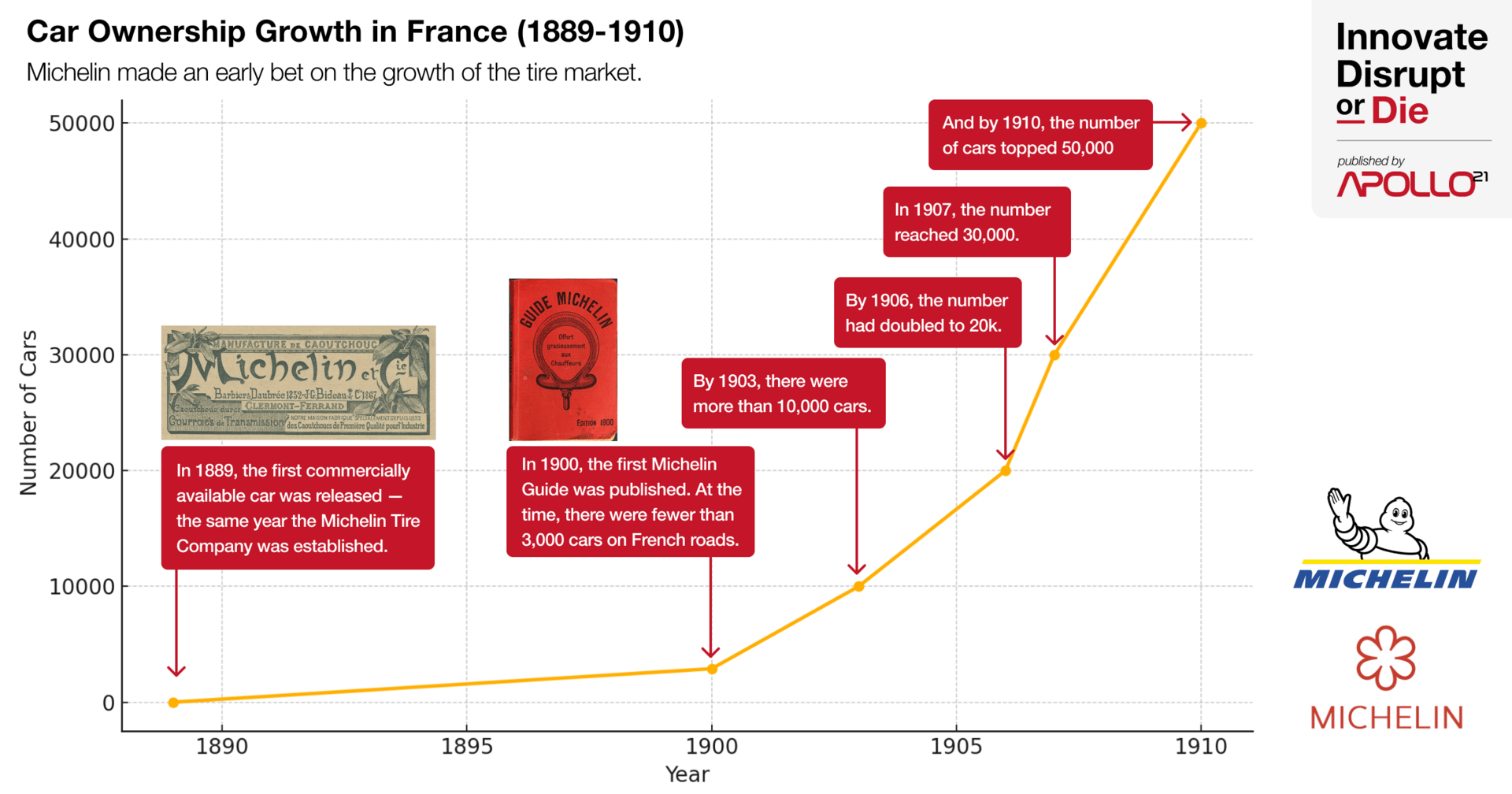

In 1900, France had roughly 3,000 cars on the road. Michelin, then a newly minted tire company, had a product few people needed. So instead of focusing their innovation efforts on improving that product, they turned their attention to engineering demand.

The brothers Michelin created a free travel resource: The Michelin Guide. A pocket-sized booklet that helped drivers put more mileage on their vehicles by suggesting where to go and what to do once you got there.

The logic was ruthless in its simplicity:

More driving equals more tire wear.

More tire wear equals more tire sales.

The original 400-page edition included maps, gas stations, repair tips, hotels, and even instructions for how to change a tire. It was a full-stack mobility guide, designed to make long-distance car travel less intimidating at a time when cars weren’t yet ubiquitous.

And they gave it away for free.

But something unexpected happened. Over the next two decades, one specific section of the guide, the restaurant recommendations, took on a life of its own. What started as a few listings to give travelers a reason to get back on the road became the most coveted quality signal in the global culinary industry.

By 1926, Michelin formalized the concept of the Michelin Star. By the 1930s, they had introduced the now-famous three-star hierarchy:

One star: a very good restaurant in its category

Two stars: worth a detour

Three stars: worth a special journey

That last line is where the strategy truly comes to life: encourage people to take a special journey. Michelin didn’t hide its priorities. They weren’t grading food for food’s sake. They were explicitly creating reasons for people to drive long distances.

The Michelin Star didn’t start as an award. It started as a measure of distance justification.

The Restaurant Industry Didn’t Hire Michelin.

Michelin Hired the Restaurant Industry.

Over the following decades, the Michelin Guide quietly restructured the economic incentives for restaurants across Europe. It moved dining from a local experience to a regional and even international one. The guide concentrated attention and spending on a small set of fine dining establishments.

And it placed an external commercial entity, Michelin, at the center of that ecosystem.

Today, chefs around the world alter hiring, training, sourcing, plating, and even service structure in pursuit of Michelin Stars. Entire business models are shaped by whether or not a star has been awarded.

In the restaurant world, receiving a Michelin star can create long-term demand (and revenue). But losing one can crater a restaurant forever.

The Michelin Star also comes with pressure. Stars are awarded anonymously, and they can be taken away at any time. Several high-profile chefs have gone so far as to publicly return their stars or ask to be delisted to escape the expectations and scrutiny that come with them.

Yet nearly no one associates the star with the tire company that created it. Chefs chasing the approval of a French tire manufacturer is a running joke in the food world. But this is not a branding failure. This is a strategic masterclass.

The world they live in now is in no way the world the Michelin system was set up to evaluate back in France, which was all about motorists and seeing if it was worth driving an extra 50 miles for a restaurant. It's a silly thing. Why do you want to help a tire company? You don't owe them nothing.

Michelin Built a Self-Reinforcing Demand System

What Michelin achieved is the holy grail of innovation.

They created a new market category built on behavioral change that supported their core business without requiring incremental improvements to the product itself.

They invented a reason to use the product more.

Michelin didn’t push tire sales harder. They created a new behavior (driving to dine) that increased the frequency of tire use. They solved their lack of demand not by improving the product, but by expanding the context in which the product was useful.

They constructed a cultural artifact that outlived the business rationale.

The Michelin Guide now exists almost entirely disconnected from its original purpose. The brand equity of the Star has far exceeded the utility of the guide itself. Achieving a Michelin star doesn’t bring “tire company prestige." It just brings prestige.

They set the rules of a system they don’t even operate in.

Michelin doesn’t run restaurants. They don’t cook food. They don’t employ chefs. Yet they have controlling influence over hiring, pricing, marketing, and menu construction at the highest levels of the industry.

They created cultural infrastructure and then let others build on top of it.

Jobs to Be Done: Who Was Hiring Michelin, and for What?

The Michelin Guide doesn’t answer the job “where should I eat tonight?” It answers deeper, less visible jobs:

For travelers: “Where is it worth going that justifies the time and effort?”

For chefs: “How do I validate myself in a system that rewards perfection and creativity?”

For restaurants: “How do I attract high-income customers willing to travel?”

For Michelin: “How do we create more reasons for people to travel long distances by car?”

That’s the brilliance. The same artifact solved wildly different jobs for multiple actors in the ecosystem. Michelin didn’t just build a tool. They built a system that shaped how others behave, succeed, and compete around them. The Michelin Guide became a rulebook for restaurants, even though Michelin doesn’t operate in that industry.

Most Innovation Efforts Miss the Bigger Opportunity

When teams talk about product innovation, they almost always focus on “what else can we sell” or “what else can we build.” Michelin asked something far more valuable… “What else can we cause people to do?”

Innovation teams should study Michelin not as a branding story, but as a blueprint for:

Designing demand around use-case expansion

Michelin’s guide didn’t promote tires. It promoted behaviors that would lead to more driving. That’s where most innovators fail: by trying to shift messaging or features instead of behavior.

Creating cultural capital instead of pushing product features

The Michelin Star became a signal. A badge. A scoreboard. If your innovation work isn’t creating something that people aspire to win, be part of, or align with, you’re probably solving the wrong job.

Structuring adjacent ventures to build value for the core

Too often, corporate ventures are sandboxed. They’re told to be “separate” and “disruptive,” but with no structural tie-back to the parent. Michelin didn’t separate the guide from the business. They fused them so one fed the other continuously.

The Innovation Horizon Michelin Activated

The Michelin Guide wasn’t just a marketing asset. It was a new product in a new category: travel publishing infused with ratings-based cultural authority. It didn't emerge from the core tire business, but it was engineered to serve the goals of that core business.

That puts Michelin squarely in the top-right of the Innovation Horizon diagram: new product, new category, new behavior. It’s the riskiest and most misunderstood zone of innovation (and the one most folks avoid).

Michelin didn’t avoid it. They mastered it, creating a cultural icon in the process.

The Michelin Play Still Works

Today’s execs are constantly told to think like startups. But Michelin’s play wouldn’t pass most modern filters. It wasn’t data-driven. It wasn’t a “core competency.” And it’s highly unlikely that the ROI of the original Michelin guide was measuring in quarters (or even years).

Instead of chasing ROI, they engineered ROBI: Return on Behavioral Influence. They played the long game in small-but-growing market.

They created a new kind of demand, one based on aspiration, not awareness. Looking back, it becomes clear that this is what makes it genius.

So ask yourself:

What are the behaviors that drive your business?

Who controls the culture around those behaviors?

What would it take for your company to write the rules of that game?

Michelin answered all three with a free guidebook and a few well-placed stars.

CASE STUDY

Red Bull Didn’t Sell Energy.

They Built a Culture Around Risk

Red Bull didn’t build a drink company. They built an ecosystem designed to make the drink essential. Instead of fighting for shelf space in crowded convenience stores, they engineered behavior. They backed extreme sports, launched media properties, and created events that demanded energy, speed, and risk.

The product wasn’t the centerpiece. The culture was.

They own sports teams. They produce documentaries. They host their own events like Red Bull Rampage and Flugtag. They fund athlete careers. Red Bull sets the rules of a culture they profit from, without needing to manufacture every moment.

In doing so, they created reasons for people to aspire to drink Red Bull. Just like Michelin gave drivers destinations to justify long journeys, Red Bull gave their target customers a sense of identity to justify daily consumption.

You’ll rarely hear Red Bull talk about flavor, ingredients, or function. That’s the point. They aren’t selling the drink. They’re selling a worldview. The drink just happens to be the most convenient on-ramp.

That’s the Michelin playbook: create cultural infrastructure that makes your product feel like a requirement for entry. Michelin gave us distance-worthy restaurants. Red Bull gave us flight-worthy lifestyles.

How did this edition land for you?

Remember: you can innovate, disrupt, or die! ☠️

Have you seen our free resources?

Apply to be a podcast guest!

Spread the word on your latest innovation…

Know an innovator who needs this?

Was this email forwarded to you?